What are Docker images and containers?

I'm sure you have heard of the term "Virtual Machine". A virtual machine is an emulation of an Operating System. For example, if you run a Windows virtual machine on your MacOS computer, it will run a whole copy of Windows so you can run Windows programs.

This diagram shows what happens in that case:

When you run a Virtual Machine, you can configure what hardware it has access to (e.g. 50% of the host's RAM, 2 CPU cores, etc).

Docker containers are a bit different because they don't emulate an Operating System. They use the Operating System kernel of your computer, and run as a process within the host.

Containers have their own storage and networking, but because they don't have to emulate the operating system and everything that entails, they are much more lightweight.

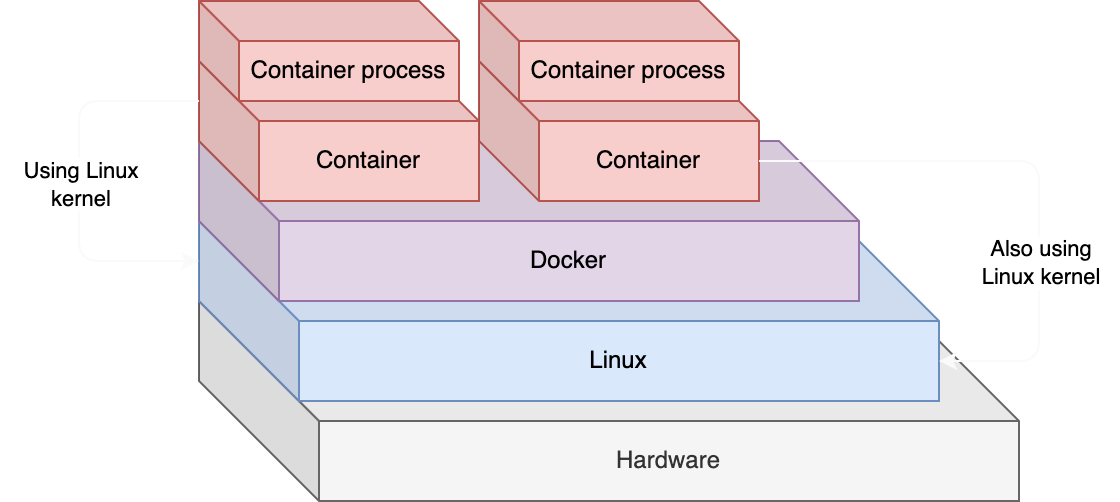

This diagram shows how Linux containers run in a Linux host:

Looks similar, but the docker -> container section is much more efficient than running a VM because it uses the host's kernel instead of running its own.

What is a kernel? 🍿

An Operating System is made up of two main parts:

- The kernel

- Files and programs that come with the operating system

The Linux kernel, for example, is used by all Linux Operating Systems (like Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, etc.).

Since containers use the host's kernel, you can't run a Windows Docker container natively in a MacOS host. Similarly, you can't run a Linux container natively on Windows or MacOS hosts.

How to run Linux containers on Windows or MacOS?

When you use Docker Desktop (which I'll show you in the next lecture), it runs a Linux Virtual Machine for you, which then is used to run your Linux containers.

But aren't you then doing this?

hardware -> macos -> hypervisor -> linux vm -> docker -> container -> container program

And isn't that much less efficient than just running the program in a Linux virtual machine?

Yes. Running Linux containers on MacOS or Windows is "worse" than just running the programs in a Linux VM. However, 99% of the time, you will be running Linux containers in a Linux host, which is much more efficient.

When you want to deploy your applications to share them with your users, you will almost always be running your app in a Linux server (provided by a deployment company, more on that later). There are a few reasons for this. Among them, Linux is free!

Why are containers more efficient than VMs?

From now on let's assume we are running native Linux containers in a Linux host, as that is by far the most common thing to do!

When you run a VM, it runs the entire operating system. However, when you run a container it uses part of the host's Operating System (called the kernel). Since the kernel is already running anyway, there is much less work for Docker to do.

As a result, containers start up faster, use fewer resources, and need much less hard disk space to run.

Can you run an Ubuntu image when the host is Linux but not Ubuntu?

Since the Linux kernel is the same between distributions, and since Docker containers only use the host's kernel, it doesn't matter which distribution you are running as a host. You can run containers of any distribution with any other distribution as a host.

How many containers can you run at once?

Each container uses layers to specify what files and programs they need. For example, if you run two containers which both use the same version of Python, you'll actually only need to store that Python executable once. Docker will take care of sharing the data between containers.

This is why you can run many hundreds of containers in a single host, because there is less duplication of files they use compared to virtual machines.

What does a Docker container run?

If you want to run your Flask app in a Docker container, you need to get (or create) a Docker image that has all the dependencies your Flask app uses, except from the OS kernel:

- Python

- Dependencies from

requirements.txt - Possibly

nginxorgunicorn(more on this when we talk about deployment)

The keen-eyed among you may be thinking: if all you have is the kernel and nothing else, aren't there more dependencies?

For example, Python needs the C programming language to run. So shouldn't we need C in our container also?

Yes!

When we build our Docker image, we will be building it on top of other, pre-built, existing images. Those images come with the lower-level requirements such as compilers, the C language, and most utilities and programs we need.

What is a Docker image?

A Docker image is a snapshot of source code, libraries, dependencies, tools, and everything else (except the Operating System kernel!) that a container needs to run.

There are many pre-built images that you can use. For example, some come with Ubuntu (a Linux distribution). Others come with Ubuntu and Python already installed. You can also make your own images that already have Flask installed (as well as other dependencies your app needs).

In the last lecture I mentioned that Docker containers use the host OS kernel, so why does the container need Ubuntu?

Remember that operating systems are kernel + programs/libraries. Although the container uses the host kernel, we may still need a lot of programs/libraries that Ubuntu ships with. An example might be a C language compiler!

This is how you define a Docker image. I'll guide you through how to do this in the next lecture, but bear with me for a second:

FROM python:3.10

EXPOSE 5000

WORKDIR /app

RUN pip install flask

COPY . .

CMD ["flask", "run", "--host", "0.0.0.0"]

This is a Dockerfile, a definition of how to create a Docker image. Once you have this file, you can ask Docker to create the Docker image. Then, after creating the Docker image, you can ask Docker to run it as a container.

Dockerfile ---build--> docker image ---run--> docker container

In this Dockerfile you can see the first line: FROM python:3.10. This tells Docker to first download the python:3.10 image (an image someone else already created), and once that image is created, run the following commands.

The python:3.10 image is also built using a Dockerfile! You can see the Dockerfile for it here.

You can see it comes FROM another image. There is usually a chain of these, images built upon other images, until you reach the base image. In this case, the base image is running Debian (a Linux distribution).

Where is the base image!?

If you really want to go deep, you will be able to find...

- The

python3.10:bookwormimage builds onbuildpack-deps:bookworm buildpack-deps:bookwormbuilds onbuildpack-deps:bookworm-scmbuildpack-deps:bookworm-scmbuilds onbuildpack-deps:bookworm-curlbuildpack-deps:bookworm-curlbuilds ondebian:bookwormdebian:bookwormlooks really weird!

Eventually, the base image has to physically include the files that make up the operating system. In that last image, that's the Debian OS files that the maintainers have deemed necessary for the bookworm image.

So, why the chain?

Three main reasons:

- So you don't have to write a super long and complex

Dockerfilewhich contains everything you need. - So pre-published images can be shared online, and all you have to do is download them.

- So when your own images use the same base image, Docker in your computer only downloads the base image once, saving you a lot of disk space.

Back to our Dockerfile. The commands after FROM... are specific to our use case, and do things like install requirements, copy our source code into the image, and tell Docker what command to run when we start a container from this image.

This separation between images and containers is interesting because once the image is created you can ship it across the internet and:

- Share it with other developers.

- Deploy it to servers.

Plus once you've downloaded the image (which can take a while), starting a container from it is almost instant since there's very little work to do.